Johannes Willebrands: A Jewish View

by Judith Herschopf Banki

Given at the Proceedings Centenary Conferences (Utrecht and Rome) in commemoration of Johannes Cardinal Willebrands, 2009. Originally published by Seton Hall University.

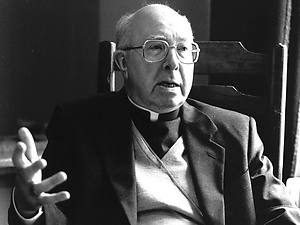

Johannes Cardinal Willebrands | Cardinal Willebrands Research Centre

Thomas Stransky has noted in his brilliant preface to the Willebrands diaries, “it is impossible to understand modern Catholicism, indeed modern Protestantism and Eastern Orthodoxy, without taking into account Vatican II.” [I would add that it is also not possible to understand the contemporary Jewish community and the broad field of Jewish-Christian relations without taking into account the changes wrought by Vatican II.] But, he goes on to note, “it is also true that this ‘convulsive alteration of the whole religious landscape’ (Garry Wills) took place before most of today’s Catholics and others have been born…. Vatican II promulgated SPCU documents on ecumenism, on religious freedom, on the relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions…. But for most who are interested, these … stand by themselves, without a history. The texts outlive the contexts. (emphasis mine) The end product is stripped of unpredictable and threatened journeys, of surprises, setbacks, and blessings along the way. And alas, falling back into darker shadows are the actors…”

The actors who brought about the momentous changes in ecumenical and Jewish-Christian relations that we shall review here in Utrecht are heroes without doubt. But there are heroes and heroes. Some are daring and confrontational; they leap fearlessly, perhaps even obsessively, into the struggle for justice as they see it. Resistance and hostility only sharpen their resolve and intensify their efforts. Like our biblical prophets, they are not the most patient people in the world; they have little concern about alienating people; they may make enemies along the way, and some of them pay a heavy price for their passionate commitment.

Then, there are other heroes, who put patience and fortitude to the service of progress, who are endowed with exceptional diplomatic skills, who use restraint combined with persistence to advance their goal, who understand the need to compromise without compromising away the desired end. They may not upset the apple cart, but they stay the course. They are not as confrontational, but they are steadfast.

Profound changes that shake the foundations of long-established attitudes and prejudices require both kinds of heroes, but it is clear that Johannes Willebrands was the second kind. What emerges from his diaries and from his historic role in the ecumenical movement is a man of friendly, open disposition and extraordinary patience, but with a strong backbone. One senses through his journals that he was nobody’s fool: he was frequently annoyed and occasionally outraged by the negative attitudes and obstructionist tactics of members of the curia and others who, during the Second Vatican Council, were vehemently opposed to renewal in the Church and determined to prevent it at all costs. Yet he never lost his cool. He remained civil and respectful, even to the enemies of his goals and aspirations. I suspect he never made a personal enemy.

How deeply human he was! He loved companionship and conversation, he enjoyed good meals, movies, theater, and concerts, he was very close to his family, devoted to his parents and siblings. He made lifelong friends and cherished his friendships, and – rare at the time – he had women friends and professional associates, and respected their opinions. He had a lively intellectual curiosity that was unthreatened by new ideas, although he was very solidly rooted in his spiritual tradition and sincere in his piety. He was an avid reader and actually enjoyed studying. Perhaps most remarkable, he was indefatigable, often working from daybreak until late at night. Just to read a few of his daily schedules is exhausting! In the detailed diaries and more succinct agendas covering some five years of daily work, I discovered only two days on which he counted himself “malade.” His capacity for work and his good health proved to be a blessing to those of us who benefited from his achievements.

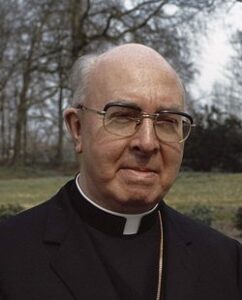

Johannes Cardinal Willebrands, 1982 | Wikipedia

He was earlier involved – and, I believe, more interested and more innovative – in ecumenical than in Jewish-Christian relations. He had contacts and connections in the Protestant and Orthodox churches long before the SPCU was created (indeed, these connections and the goodwill he had developed may explain why he received his appointment to the secretariat when it was created.) His primary interests were for building relationships with Protestant and Orthodox Christian churches. Yet, when the SPCU was given the “Jewish portfolio” in 1961, he extended his concern and commitment to the passage of what emerged from the Council, promulgated by Paul VI as Nostra Aetate, and he used his considerable diplomatic skills to negotiate with the document’s enemies and to maneuver its passage through the thickets of theological and political opposition.

His theology of Jews and Judaism was, understandably, pre-Vatican Council II. He believed that Judaism found its fulfillment in Christianity, and I believe he hoped that Jews would find their way into the Church. He might have been surprised – pleasantly, I would hope – by more recent affirmations of Catholic theologians and scholars that Judaism provides a saving faith for Jews and disclaimers of missionary intent to the Jewish community. Whatever his hopes regarding ultimate Jewish conversion to Christianity, he was staunchly opposed to antisemitism in both its religious and political dimensions, and he had an empathetic understanding of the suffering and persecution of Jews during the Shoah. Fr. Stransky notes that Willebrands’ friend and mentor, Frans Thijssen, introduced him to Catholics and Protestants who were aiding helpless refugees from the Nazis, Jews in particular, in the late 1930s. This may have been the source of his identification with Jewish experience on a human, rather than a theological level.

Because of this identification, he was quick to acknowledge and promote Church documents that corrected the negative images of Jews and Judaism still found in the Catholic tradition. On 18 October, 1977, during a discussion in the synod on religious education, he made a written intervention on the image of Judaism in Catholic teaching. (SIDIC, Documentation Collection) Drawing on official Church documents, he emphasized that it was theologically and practically impossible to set forth Christianity without reference to Judaism and that the image of Judaism used to illustrate Christianity “is rarely exact, faithful to or respectful of the theological and historical reality of Judaism.” Quoting directly from Church documents, he underscored the continuity of the two testaments, the voluntary passion and death of Christ, for which the Jewish people should not be blamed, or depicted as rejected and cursed by God, and emphasized that the history of Judaism did not end with the destruction of Jerusalem, but continued to develop a tradition-rich with religious values. Cardinal Willebrands did not invent these phrases, but he put the weight of his authority behind them. And he certainly brought his diplomatic skills to use in defending what was then called de judaeis, as well as the declaration on religious liberty, against powerful forces bitterly opposed to renewal during the course of the Council.

He was extremely cautious in his attitudes toward Israel, and may have had a falling out with his former secretary, Fr. Cornelius Rijk, over Fr. Rijk’s activities on behalf of Church recognition of Israel.

A word about myself. Like Fr. Stransky, I am a child of the Second Vatican Council – he on the Catholic side, I on the Jewish side. That is, I cut my teeth in the field of Jewish-Christian relations as part of a relatively small group of Jewish activists who mounted an initiative on behalf of an authoritative statement on Jews and Judaism to be adopted at the Council – a statement that would condemn antisemitism, repudiate the deicide charge against the Jewish people, correct teachings of contempt about Jews and Judaism, acknowledge that Judaism did not end with the emergence of Christianity but continued to develop as a living faith, and inaugurate an ongoing dialogue between the Church and the Jewish community. We further hoped these policies would be implemented through the establishment of some permanent structure within the Church.

I worked under the leadership of Rabbi Marc H. Tanenbaum, who, together with Zachariah Shuster, director of the European office of the American Jewish Committee, led this initiative. Tanenbaum also enlisted Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel in the effort, and set up meetings between Cardinal Bea, Heschel, and other Jewish religious and community leaders during Bea’s trip to the United States in 1963.

Like Fr. Stransky, I look around at the actors in that drama – and, believe me, it was a drama – what they call in movies a “cliffhanger.” From the Catholic side, he notes that almost all are gone. (Of the 2500 bishops who attended the Council, 30 were still alive as of January 2008. Of the staff of the SPCU, all of the bishops are gone; of the consultors, two remain alive; of the staff, himself and two secretaries.) From the Jewish side, those active in some sustained fashion on behalf of the so-called “Jewish decree” and the declaration on religious liberty during the Council: Tanenbaum, Heschel, Dr. Eric Werner of Hebrew Union College, (who drafted the memorandum on anti-Jewish elements in Catholic liturgy), Dr. Joseph Lichten of the Anti-Defamation League, Dr. Gerhardt Riegner of the World Jewish Congress, all have passed on. If any were still with us, I would not be standing here today. I and Rabbi Tanenbaum’s former secretary remain, somewhat battered veterans of that 50-year-old struggle. In Fr. Stransky’s poignant words, “Fifty years later we remember, misremember and forget.”

Church and Jewish People: New Considerations by Johannes Gerardus Maria Cardinal Willibrands

What struck me most going through the Willebrands’ papers – both the diary and the conciliar agendas – is how thin a slice of his time is taken up with the question that absorbed my time almost entirely. Much more of his schedule is devoted to inter-Christian relationships and the goal of Christian unity.

When John XXIII was elected to the papacy in 1958 and shortly thereafter, surprised everyone by announcing the summoning of an ecumenical council, we were approached by a French Catholic author and scholar, Mme. Claire Huchet Bishop, an ardent devotee of the work of Jules Isaac. (It was she who was largely responsible for the publication of his books in the United States, and thus, indirectly, for familiarity with the expression, “the teaching of contempt” on the North American continent.) She urged the American Jewish Committee to become involved, insofar as possible, in the forthcoming council, to engage in a vigorous initiative for the repudiation “at the highest level of the Church.” of that anti-Jewish and antisemitic tradition of teaching and preaching whereby Jews had been segregated, degraded, charged with wicked crimes, and valued only as potential converts. Ecumenical councils are few and far between, she said, and this is a historic opportunity. “Seize it.”

Another historic event added urgency to that goal. At the same time that the preparatory commissions for the Council were going about their work, the nightmarish details of the Nazi genocide against the Jews were being vividly recalled by the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem. The moral questions posed by the Eichmann trial were not lost on religious spokesmen, some of whom pointed to the need to root out the sources of hatred and contempt for Jews and Judaism for once and for all.

It soon became apparent that the key figure with regard to a “Jewish decree” at Vatican II was Cardinal Augustin Bea, and that he and his secretariat had been entrusted by Pope John to draft a statement and to seek representative Jewish viewpoints. The way was open for communication and dialogue. We at the AJC vigorously engaged in both.

On July 31, 1961, over a year before the opening of the Council’s first session, the American Jewish Committee submitted to Cardinal Bea, by prior agreement, the first of several comprehensive memoranda. Entitled, The Image of the Jew in Catholic Teaching, the 32-page document identified and illustrated slanderous interpretations, oversimplifications, unjust or inaccurate comparisons, invidious use of language and significant omissions in American Catholic textbooks, and it cited existing Catholic sources that could serve as corrections. I authored that document, based on the findings of a self-study of Catholic textbooks undertaken at St. Louis University by Sr. Rose Thering, O.P. (Transformed by the implications of her own research, Sr. Thering became an important educator in the field, serving with Msgr. John Oesterreicher at the Center for Judaeo- Christian Studies at Seton Hall University. She was also a lively activist on behalf of Israel, and led over fifty study tours to the Jewish state.)

On November 17, 1961, a second memorandum, Anti-Jewish Elements in Catholic Liturgy, was submitted to Bea. While acknowledging the recent deletion of problematic passages in the liturgy, the document noted that the concept of Jews as deicides still figured in some liturgical passages, in popular and scholarly commentaries on the liturgy, and in homiletic literature.

In December 1961, Professor Abraham Joshua Heschel met with Cardinal Bea in Rome. (Since there are no Willebrands diaries for that period – or, at least, none have been found – we do not know whether Willebrands was present at the meeting.) One of the outcomes of that meeting was an invitation for Heschel to submit suggestions for positive Council action to improve Catholic- Jewish relations. In May 1962, he followed up with a memorandum, prepared in cooperation with the American Jewish Committee, recommending a number of specific actions: forthright rejection of the deicide charge against the Jewish people, recognition of Jews as Jews, (rather than as potential converts) promotion of scholarly and civic cooperation, and the creation of church agencies to help overcome religious prejudice. (None of these documents are mentioned in the Willebrands diaries or agendas, but as Bea’s close assistant, it is likely he read them.)

Like Fr. Stransky, I find Willbrands’ entries frequently rich in daily details (appointments, lunches, conversations with specific personalities) and yet lacking in theme and substance. (What were the conversations about? Who said what to whom? What is ignored or overlooked?) (Stransky notes that Willbrands mentions routine luncheons with staff colleagues at a local restaurant, but fails to note the date of a working audience with Pope Paul VI; a long, revealing conversation about the difficulties of drafting De Judaies is narrated by Yves Congar in his own writings, yet the Willebrands agenda lists nothing for the same day. It is somewhat frustrating to find these lacunae, but some of them may have been due to his sense of discretion about very inflammatory issues.

In a similar fashion, Cardinal Willbrands notes his three trips to the Middle East in 1965: the first, March 18-23, accompanied by Fr. Duprey, to Beirut, where he met with Catholic, Armenian, Syrian, and Greek Orthodox patriarchs and other clergy, and with the papal nuncios to Lebanon and Syria; the second, April 22-30, accompanied again by Fr. Duprey, to Beirut, Jerusalem, Cairo and Addis-Abeba, where he met with Catholic, Orthodox, Anglican church leaders and ambassadors; and the third, apparently at the request of the pope, July 19-24 – after the text of the Jewish declaration had already been modified to eliminate the word, “deicide” and the expression “condemn” referring to antisemitism — to Beirut, Jerusalem and Cairo, accompanied by Fr. Duprey and this time, also by Msgr. De Smedt. Again, they met with a variety of Catholic, Orthodox and Anglican church leadership.

Although Willebrands’ journals do not specify the purpose of these visits, we know for a fact that it was to try to overcome Arab hostility and objections to the statement on the Jews. In the third trip, he was partly successful.

The vehemence and vitriol of the Arab hostility still astonish me. From an almost fifty-year post- Vatican II perspective, reading the objections raised by Arab government and religious leadership to any effort by the Church to lift an accusation “of infamy and execration,” in the words of Bishop Stephen Leven of San Antonio, Texas, which “was invented by Christians and used to blame and persecute the Jews … for many centuries, and even in our own…” still sets my teeth on edge.

As I wrote in an article in the American Jewish Year Book, 1966 (“The Church and the Jews: The Struggle at Vatican Council II”): “The interest of the Arab world in the charge of deicide against Jews cannot be attributed to religious concern: the question is of little or no consequence to Islam. The Arab opposition to any statement expressing esteem or affection for Jews, suggesting a special relationship between Christianity and the Jewish people, deploring specific acts of persecution against Jews, and removing a theological basis of antisemitism is politically motivated, and this opposition has been carried out on the highest political and diplomatic levels.” Indeed, the campaign included threats of reprisals against Christian minorities in Arab lands. These never materialized.

If we did not know the specifics of this vitriolic campaign from other sources, we would not have derived them from Cardinal Willebrands journals of his visits to the Arab world.

In addition to the Arab initiatives, there was a sustained campaign against the so-called Jewish declaration on doctrinal grounds by conservative elements within the church who believed that Jews, as a people, did indeed bear collective responsibility as deicides and that their suffering across the ages was proof of providential punishment for this crime. Representatives of this position may have constituted only a small minority within the Council, but they had access to extraordinary channels of distribution. Thus, a few days before the conclusion of the second Council session, every prelate found in his mailbox a privately-printed 900-page volume, Il Complotto contro la Chiesa (“The Plot Against the Church”) filled with the most primitive anti- Semitism. Described by Msgr. George Higgins, a columnist for the National Catholic Welfare Conference’s press service as “a sickening diatribe against the Jews,” it charged that there was a Jewish fifth column among the Catholic clergy, plotting against the Church, and it even justified Hitler’s acts against the Jews. The “fifth column” accusation was undoubtedly directed at converts from Judaism who were associated with Bea’s secretariat and who played some role in the drafting of the declaration, such as Fr. Gregory Baum and Msgr. John Oesterreicher, both of whom had written widely on issues of Jewish-Christian relations. (During the third session of the Council, America’s most famous home-grown antisemite, the Protestant Gerald L.K. Smith, wrote to all American bishops offering to supply them, free of charge, with an English translation of the very same book. His four-page letter claimed that the American bishops had been taken in “by a fraternity of deceivers too close to the centers of authority in the affairs of the church.”) Revisiting the paranoia of the ultra-right and the fierce opposition of the Arab world, we must admire Willebrands for having steered a cautious but determined course between them. Yet, these antisemitic eruptions are not mentioned in his agendas, although those of us in the Jewish community who followed the tortured path of the statement on the Jews were very much aware of them.

In March 1963, Cardinal Bea, accompanied by Willebrands and Fr. Schmidt, visited the United States to lecture at Harvard University. Subsequently, he was honored at an interfaith agape in New York City devoted to the theme, “Civic Unity Under God.” He used that occasion – attended and addressed by such personalities as U Thant, Zafrulla Khan, N.Y. State Governor Nelson Rockefeller, New York City Mayor Robert F. Wagner, Henry Luce, Dr. Henry Pitney Van Dusen, Cardinal Richard Cushing, Greek Orthodox Archbishop Iakovos, and Rabbi Heschel – to issue an affirmative statement in support of freedom of conscience. The document on religious liberty being another “hot potato” at the Council, his comments were viewed as explicit support for a forthcoming declaration.

But Bea’s visit was also the occasion of an unpublicized and unprecedented meeting with a group of Jewish religious leaders – representing Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform branches of Judaism – held at the AJC’s headquarters on March 31. Responding to prepared questions regarding the prospects for Council action on Jewish concerns, Bea declared that the events of the Passion could not be charged against Jewry as a whole; that it was necessary to clarify the true sense intended by the writers of the New Testament; that there was a need for interreligious communication and cooperation, and that his views were endorsed by Pope John.

This meeting, whose candor and substance were considered deeply important – and encouraging– for those in the Jewish community engaged in the Vatican Council initiative, is referenced by Willebrands only as “Conversation au Jewish Committee.” (On the following day, he notes a discussion with Heschel at the Jewish Theological Seminary.)

A Prophet for Our Time – A Selected Anthology of the Writings of Rabbi Marc H. Tanenbaum

Fortunately, Willbrands has provided us with a fuller and richer recollection of that event in his Introduction to Marc Tanenbaum’s biography (A Prophet for Our Time: A Selected Anthology of the Writings of Rabbi Marc H. Tanenbaum, ed. Judith Hershcopf Banki and Eugene J. Fisher, Fordham University Press, 1996):

“I met Rabbi Marc Tanenbaum for the first time in New York on a Sunday afternoon, March 31, 1963, on the occasion of a meeting of Jewish scholars with Cardinal Bea. [He] was Director of the Department of Interreligious Affairs of the American Jewish Committee and convened the meeting that was chaired by Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel.

“I shall never forget that meeting, not only the setting and the historical happening but especially the atmosphere, characterized by Cardinal Bea as ‘excellent and fraternal.’ The Jews present were fairly representative of the various existing religious currents within Jewish life. Rabbi Tanenbaum told Fr. Schmidt, Cardinal Bea’s private secretary, ‘It is a miracle, not that these people met with the cardinal, but that they met with each other.’ Nevertheless, it was the person of Bea and the hope that the Vatican Council would lead the Catholic Church to a new insight and attitude regarding the relations between the church and the Jewish people that brought the Jewish dignitaries together. I felt a sense of awe for the presence of God among us. To me, it was clear that we had broken new ground, that a new era had begun in the relations between the church and the Jewish people.”

Another recollection of Cardinal Willbrands seems most apt to conclude this paper. It took place in Rome, probably at the time when the Jewish statement was under attack by theological and political opponents and its outcome uncertain. In his own words:

“One of the most significant and moving events of my life occurred on a Saturday evening when I had already made my prayers for the preparation of the Sunday. The bell rang. I was not expecting any visitors and was very surprised to see Rabbi Tanenbaum. He had come right from the celebration of the Sabbath in the synagogue. In my study, he embraced me, opened an embroidered cover from which he took out his tallith and put it over my head and shoulders. I could not say a word. By this gesture, he wished to share with me and to involve me in his prayers. For a moment I remained silent and embraced him. Our relationship was not only one of common study and interest, but it included our relation to God. We wanted together to stay before God and to invoke His blessing. His grace.”

I leave you with that picture: Cardinal Willebrands draped head and shoulders in Marc Tanenbaum’s tallith, the two of them asking God’s blessing on their sacred mission.

In our tradition, we say: zeher zadik l’vracha, the memory of the righteous is a blessing. May the memory of Johannes Willebrands, a righteous man, bless the work we still have to do together.