Daniel Green is the Conflict Resolution and Peacebuilding Intern at Tanenbaum. A note from Daniel: As a Tanenbaum intern, I have the unique privilege of participating in Peacemaker in Action Network calls every few weeks. Pastor James of Nigeria provided an update on Nigeria that had me curious about the dynamics of conflict in his region. Below is a researched account of the current multidimensional conflicts in Nigeria through the lens of Pastor James and Imam Ashafa’s latest efforts.

Violence in Nigeria is mounting to a point of crisis, and the Boko Haram insurgency only accounts for a fraction of it. In central Nigeria, an ongoing conflict between semi-nomadic herdsmen and farmers has swelled in recent years. Over the last four years, the frequency and severity of violence have persisted at alarming rates, with 3,600 deaths between January 2016 and October 2018. Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari’s government has been blamed for a paucity of state intervention, and in some cases, for allowing the assailants de facto “impunity.” In a vacuum of law, order, and prosecution, attacks and reprisals are carried out by both communities.

Tanenbaum Peacemakers in Action Pastor James Wuye and Imam Muhammad Ashafa work throughout Nigeria and the world. Some of their work takes them to the sites of these atrocities, to the interstices of warring groups. Leading their Interfaith Mediation Centre, the duo preaches peace and forgiveness in an attempt to reroute the lives of young militants and shift the bellicose ideologies of the old. However, peacemaking in this climate is particularly onerous.

Tensions first arose between herders and farmers in Nigeria in association with ecological and geographical challenges. As the majority Muslim Fulani herdsmen historically grazed their cattle in the northern Sahelian belt, which borders the Sahara Desert, their communities were the first affected by increasing drought and desertification. Contemporaneously, Boko Haram has carried out regular attacks in the North, extorted protection money from locals, and recruited younger residents for radicalization. With few alternatives, herders have moved their cattle southward, where ecosystems range from “derived savanna”–forest cleared for cultivation–to humid forests. Complicating the issue further, Nigeria’s population has surged since the mid-twentieth century: from 57 million in 1963, to 198 million in 2018. The U.S. government projects that between 2016 and 2050, Nigeria’s population will grow from 186 million to 392 million, making it the world’s fourth most populous country. In order to account for increasing food demand, farm settlements have expanded rapidly, swallowing up more and more tenable land. Thus, with herds encroaching on the prized arable central and southern regions of Nigeria, an almost Malthusian struggle over land and resources ensued.

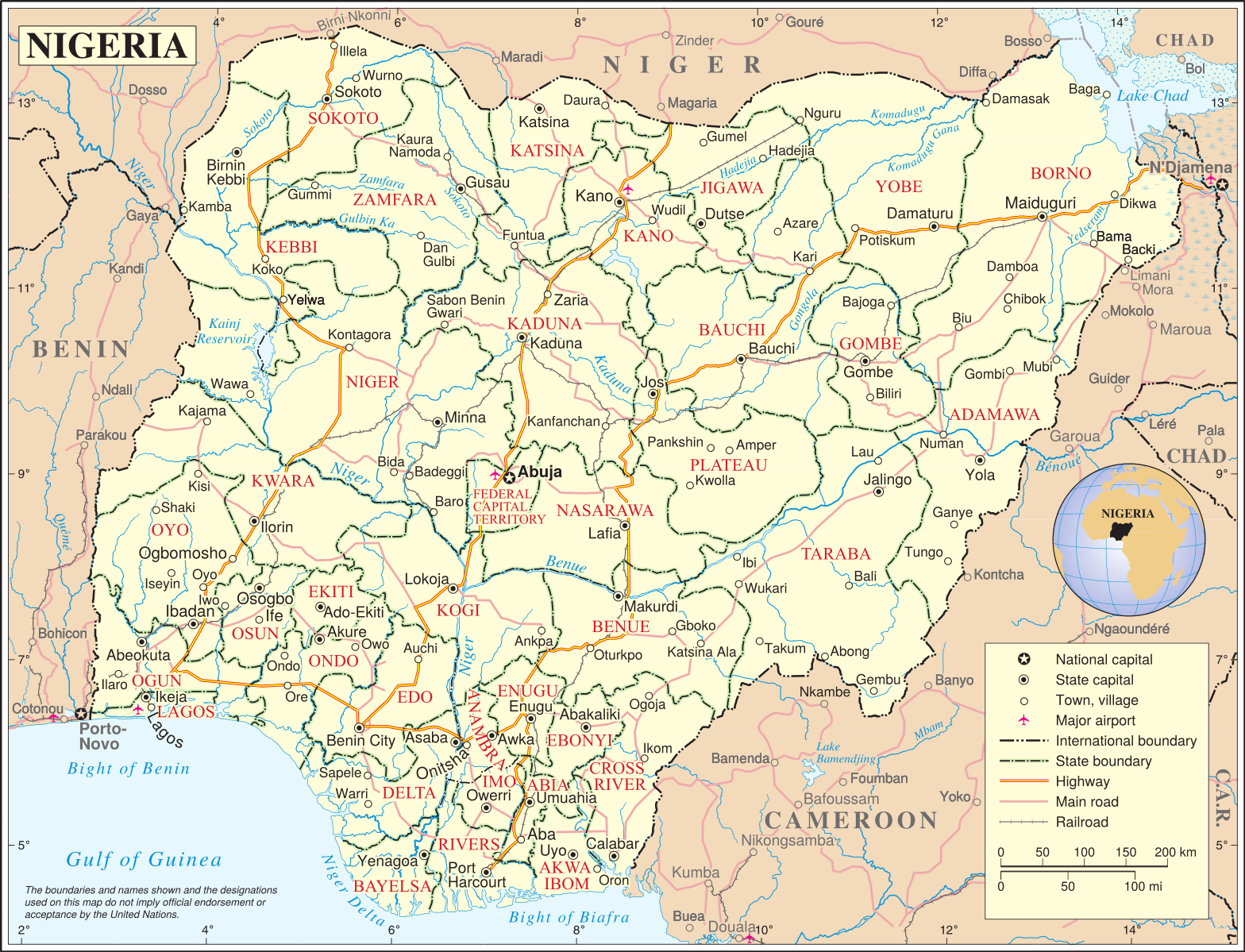

A majority of assaults unfold over the so-called Middle Belt, a swath of land comprising several latitudinally central states. Those most affected lie to the center-east: Benue, Adamawa, Plateau, Nasarawa, and Taraba States, as well as Kaduna State, where Pastor James and Imam Ashafa base their operations. In mid-2018 the International Crisis Group (ICG) reported a spike in violence. Over 1,300 deaths between January and July of that year were attributed to clashes associated with herders and farmers. Over the same period, ICG estimated the displacement of approximately 300,000 individuals. After ICG’s 2018 report was published, a portentous statistic surfaced throughout Western reports on Nigeria’s tribulations: as of July, the “farmer-herder” violence had become six times deadlier than Boko Haram’s ongoing insurgency. The surge in violence has deeply troubled Pastor James and Imam Ashafa, who call ceaselessly for young Nigerians to lay down their arms and to accept forgiveness. However, amid the tangible horrors, a discursive polarization has further threatened the prospect of peace.

For Pastor James and Imam Ashafa, conflict mediation became more complicated when an ethno-religious element entered popular discourse. As Pastor James remarked in a recent Peacemakers in Action Network call, the conflict “has taken a new dimension.”

“Especially in regions where Christians are dominant, these attacks are perceived to be motivated by some form of religion,” Pastor James explained on a March 20th Peacemakers in Action Network call. Assailants often attack sacred places, he said, kidnapping pastors with the idea that ransom money can be extracted from their congregations. Targeting a community “of the cloth” serves a dual purpose–if not only to extract funds, to disintegrate its social standing and organizational capacity. With such a high rate of attacks on religious institutions it is not inconceivable that largely Christian farming communities would tend to perceive these brutal assaults as religiously motivated and targeted. After all, the Muslim Fulani represent about 90% of Nigerian pastoralists.

“However,” said Pastor James, “this does not stop at only Christian communities. In Muslim communities in the north of Kaduna State, [armed bandits] are also killing people, rustling cattle, raping women, kidnapping for ransom and taking the money, sometimes killing the captives after the money is received.” The distinction, Pastor James argued, is that these attacks in the northern states are not given a “religious coloration,” whereas attacks in Christian communities are. On an earlier call, in January 2020, Pastor James argued that the Islamic State in West Africa (ISWA), a Boko Haram affiliate, is vying for religious war in Nigeria. “ISWA is trying to instigate interreligious violence by killing their victims and saying they are killing them because they are Christian,” James said. Regardless of these discursive colorations, members of all communities are victims.

Crucial to an accurate understanding of this conflict, or these conflicts, is a conception of multidimensionality. In fact, when Pastor James remarked that the violence had “taken a new dimension,” what he meant was that it had taken yet another dimension. Media outlets have struggled to approach the crisis in Nigeria with nuance and tact. Western publications as reputable as the New York Times and the Washington Post have been criticized for their portrayal of African (and Asian) conflicts as black and white confrontations, as Manichean divides. This style of war reporting, in which two antagonistic sides are framed in intractable war, can have adverse effects on the potential of reconciliation and peace. In this case, lines have been increasingly drawn along religious affiliations. Even the Los Angeles Times published an article titled, “Guns, Religion and Climate Change Intensify Nigeria’s Deadly Farmer-Herder Clashes.” It is because of and against these circumstances that Pastor James Wuye and Imam Muhammad Ashafa call for peace at the grassroots level.

The duo’s plea is twofold. First, they argue that spirituality is essential to the process of reconciliation, not to the mechanics of conflict. The predominately Muslim Fulani herders, and the majority Christian farmers cannot be construed as two monolithic groups. Many among their ranks share a longing for peace. “[A] thing that religious leaders can do is to call for prayer regularly in their places of worship and also have time to educate the people on how to be safe, where to go, what to say and what not to say,” Pastor James said. Religious leaders have an enormous capacity to organize individuals at the community level, and in a country whose government and security forces intervene in conflicts only selectively, this mechanism is crucial to the peace process. Further, by “what to say and what not to say,” Pastor James does not mean that Nigerians ought to abdicate their freedom of speech to local churches and mosques. Rather, he posits that religious leaders can educate communities on how to discuss the violence that unfolds before them. This brings us to Imam and Pastor’s other point.

The second prong of the duo’s appeal is discursive. Because the violence in the Middle Belt and northern states is multidimensional, Nigerians must refrain from frivolously dispensing blame on this and that group. As Pastor James explained, violence reverberates in Fulani and Christian communities alike, be it wrought by cattle rustlers, armed kidnappers, farmers, herders, Boko Haram militants or any sort of violent profiteer. “Together, those who are concerned about the safety of their people can come together and condemn the attacks of violence against every individual and call them criminals, not by calling them by a particular name, but by calling them criminals and rejecting that action,” Pastor James urged.

The ideology and theology of Pastor James and Imam Ashafa’s peacebuilding is predicated on the fundamental equality of individuals, the recognition of their humanity, and the mutual respect or perhaps even love on which it is based, and to which it leads. Agapé, it has been called. It is a concept with which all Tanenbaum Peacemakers in Action are intimately familiar. It is an idea that will prove a crucial component in reconciling Nigeria’s disheartened communities.

By Daniel Green